The thread about the Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen; a force of very doubtful military significance

Today’s Auction House Artefacts are a pair of silver Georgian merit medals awarded to Fletcher Yetts of the Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen. Mr Yetts (1759-1832) was the keeper of the City Water Works on the Castlehill. Britain was almost continuously at war with France for between 1793 and 1815 and the quaintly named Spearmen were one of the variety of amateur paramilitary formations raised in Edinburgh during this period in anticipation of a French invasion (or a popular revolution in the French style).

Front and rear views of a George III silver medal of the Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen , dated 6th August 1804. The reverse is engraved “Reward of Merit, 1st Battn., Fletcher Yetts”. Move the slider to compare each side. Photo by Gorringe’s of East Sussex.

The Volunteer Corps Act of 1794 authorised the formation of volunteer paramilitary forces for home defence; the Volunteers. These were an infantry force that generally drew their officers from petty gentry and aspirational middle-class professionals. They were distinct from the volunteer cavalry of the Yeomanry whose members were the country landowners and required to have deep pockets and horses at their disposal – and be competent in their use.

George III silver medal of the Edinburgh Spearmen Artillery Company, dated 1805. The reverse is engraved “presented by Captain Braidwood to Serjt. [sic] Major Yetts as a mark of respect for his Unremitting Attention to the Company”. Move the slider to compare each side. Photo by Gorringe’s of East Sussex.

In Scotland a third force was the Militia, established by the Militia Act of 1797 which empowered the Lords Lieutenant of the Counties to raise by ballot a conscript auxiliary force for service within Scotland. Its ranks were generally drawn from the lowest rungs of society and the Act was so thoroughly unpopular that it provoked widespread rioting across the country. This led to the Massacre at Tranent in August 1797 when eleven men, women and children were killed by Dragoons when protesting against it.

“The Massacre of Tranent”, statue by David Annand in Tranent Civic Square. This represents Jackie Crookston, one of those killed during the anti-militia protests, carrying a drum to call out the slogan of “no militia”. Image via ArtUK

In contrast to the Militia, the ranks of the Volunteers were drawn largely from the lower middle and upper working classes; an attraction of joining being it could exempt one from being drafted into the Militia. Apart from a small number of drill sergeants and drummers, the Volunteers were unpaid but received their weapons and allowances for uniforms from the Government.

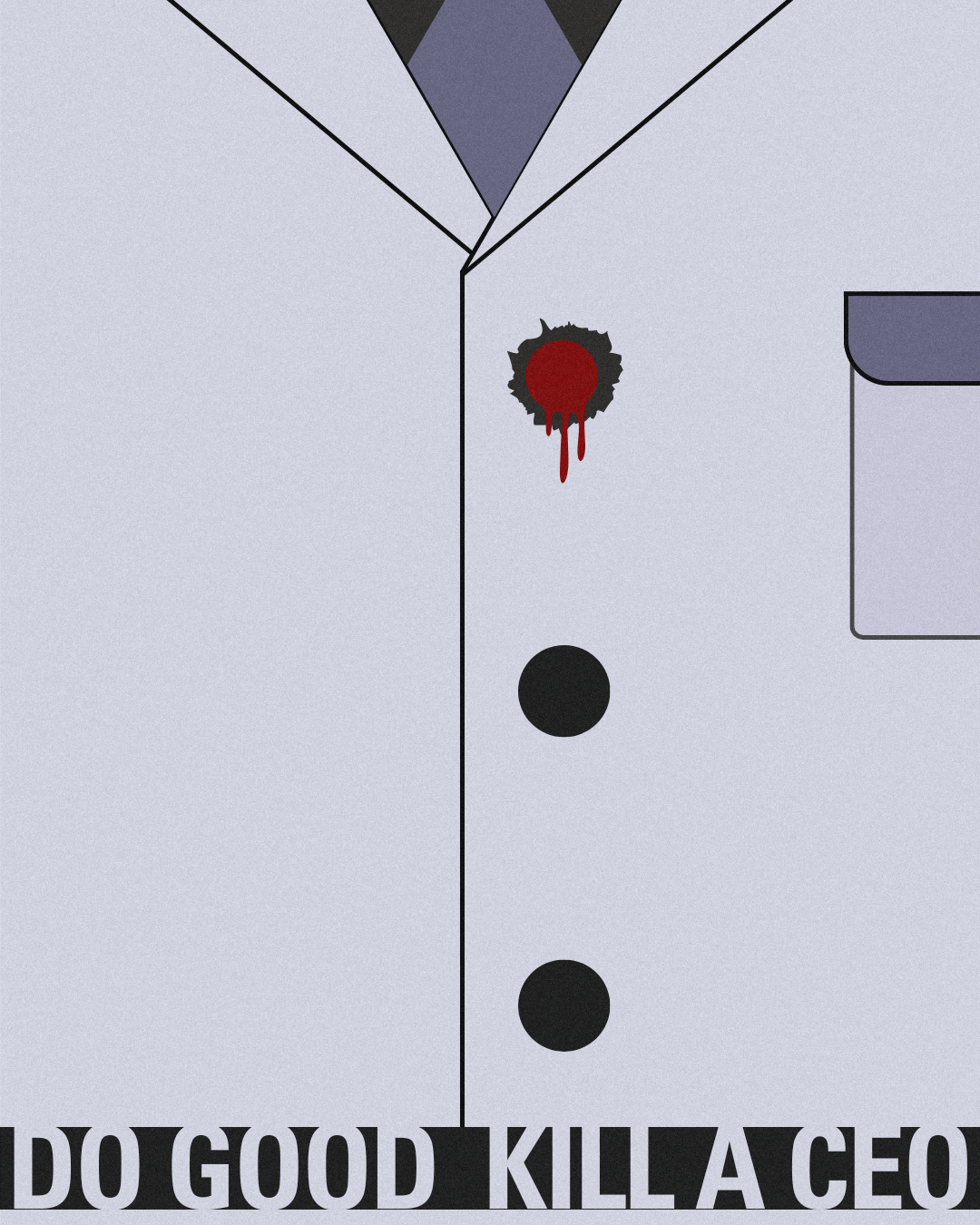

“The First Regiment of Royal Edinburgh Volunteers”, a sympathetic caricature of a parade “hereby dedicated to all the Volunteer Corps in Great Britain by their Humble Servant J. Jenkin.” 1802. National Library of Scotland

The Volunteers allowed patriotic and aspirational amateurs to play at being military officers without facing the dangers and hardships of actual military service. There was a steady supply of men keen to sport the over-embellished uniforms – and even finance the units at their own expense – to reap the benefit of the high public status that a uniform conferred in the ballrooms and drawing rooms of the city.

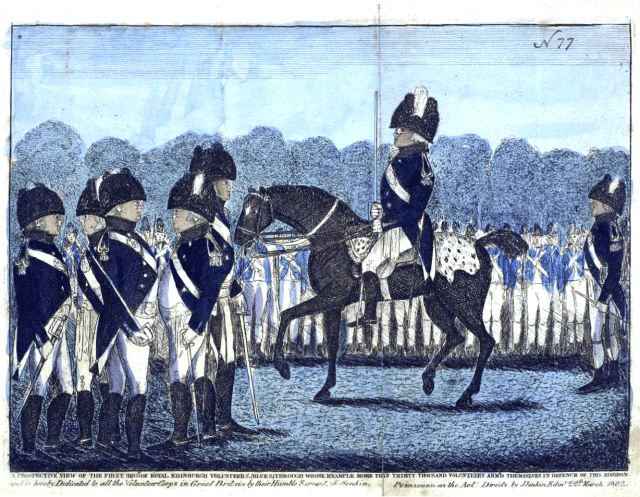

“The Grand Inspection”, caricature satirising Edinburgh volunteer officers being inspected by a lady; the inference being their patriotic service can be reduced to dressing up for her approval. By J. Jenkin, 1805. National Library of Scotland.

By late 1803, there were some 30,000 Volunteers in Scotland (and over 300,000 in the wider UK) but their efficiency varied widely; from semi-competent to completely hopeless. Georgian satirists mercilessly lampooned them, depicting them as physically unfit; poorly equipped, trained and led; over-enthusiastic and thoroughly incompetent.

“St. George’s Volunteers. Charding down the French Bond Street, after clearing the Ring in Hyde Park & Storming the Dunghill at Marylebone”. Colour caricature of 1797 by James Gillrary mocking the Volunteers. In common with other such pieces, the over-enthusiasm, poor training, poor physical condition and ill-fitting and low quality nature of uniforms are highlighted. British Museum 1851,0901.850

In their distinctive blue coats the Royal Edinburgh Volunteers (REV) were one of the first established in the country and were an example of the semi-competent type of unit. A commissioned portrait of them certainly reflected this, Edinburgh caricaturist John Kay took a slightly more humours view of them.

To see ourselves as others see us. Two very different characterisations of the late 18th century Royal Edinburgh Volunteers, both featuring Sergeant Major Patrick Gould (who in his defence was at least recognised in his time as being thoroughly competent).

The Spearmen – in contrast to the REV – showed “all the signs of being a force of very doubtful military significance” (W. A. Thorburn, curator of the Scottish United Services Museum, writing on the subject in the Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, vol. 32). They probably formed as a result of the officer corps of the other city’s other Volunteer units being fully subscribed to and thus a further unit was required for those left out. Its stated purpose was to “defend the city, liberties and vicinity of Edinburgh, in case it be found necessary to march the other forces to a distance, and to protect the lives and property of the inhabitants from injury and depredation“. This was a coded recognition that the job of the Volunteers wasn’t really to fight the (real or imagined) threat posed by French invaders but to release regular forces to do so by securing the home front. A secondary and more realistic proposition was quelling popular revolt or opportunistic disorder in the absence of the regulars: to the local authorities and certain sections of society, the Mob invoked far more fear than the French did – as evidenced by their actions at Tranent – and the Toun Rats (the Town Guard of Edinburgh) had proved of dubious worth in the past.

The Edinburgh Town Guard, painting attributed to William Home Lizars in 1800, but Lizars was an engraver and this is likely the work of (or after) John Kay. The sergeant carries a halberd but the men have muskets and bayonets. The drummer carries a short sword. City Art Centre, Edinburgh Museums and Libraries

The nascent Spearmen offered their services to the Crown, to make sure they were officially recognised and their officers Gazetted, and they were admitted as supernumeraries to the existing Volunteer establishment in the city in a letter dated 7th November 1803.

We are well persuaded that every man who can handle a pike and who is not engaged in any volunteer corps, will chearfully [sic] embrace this opportunity of coming forward for the defence of our families and firesides

Scots Magazine, December 1803

The initial plan was to raise two Battallions, each of six-hundred men in ten companies; in theory over 1,200 men. In practice however only one Battallion was ever constituted and its ranks fluctuated between four to five hundred men. They wore scarlet cutaway jackets, blue breeches and a tall beaver hat decorated with feathers (as per the medal at the top of the page and in contrast to the long blue coats and white breeches of the REV). Initially they were armed with nothing more than short pikes and swords for the officers. Their ranks were drawn largely from those exempt from balloting into the militia; the Incorporated Trades of the City and those too old, too young or with too many dependent children.

Mr John Bennet, surgeon to the garrison of Edinburgh Castle and President of the Royal College of Surgeons, was elected as the honourary Lieutenant Colonel Commandant. He had been the surgeon to the Sutherland Fencibles (an earlier, auxiliary military force in the Highlands) from 1779-83 so was an eminent choice. He was later replaced by William Inglis WS Esq. after being found dead in a field in Fife on October 10th 1805, his gun by his side, having suffered a fatal fall from his horse when hunting.

Caricature of John Bennet in his uniform, by J. Jenkin, 1804. National Library of Scotland.

Other officers included Robert Dundas and John Peat, Writers to the Signet (solicitors); William Ranken, a Town Councillor from the Incorporation of Tailors; the lighthouse engineers Thomas Smith and his step-son Robert Stevenson; Francis Braidwood, an upholsterer and cabinet-maker (and allegedly the first man in Edinburgh to wear shoelaces); John Cameron, Deacon of the Tailors and James Newton, Deacon of the Incorporation of Bakers. Their chaplain was the Reverend Alexander Brunton of New Greyfriars Kirk, later the Professor of Hebrew and Oriental Languages at the University of Edinburgh.

“Mr Dundas”, caricature by J. Jenkin, c. 1803. Given the cut of the uniform, with the short coat distinct from the other Volunteer units, and the beaver hat, this may be Major Robert Dundas of the Spearmen. National Library of Scotland.

RankNamesLieutenant ColonelJohn Bennet (died October 1805, later William Inglis)MajorRobert Dundas WS (resigned August 1805, replaced by James Farquharson)CaptainsWilliam Ranken; John Simpson; Thomas Smith; Francis James Braidwood; John Cameron; James Newton; Patrick Mellis; Alexander GairdnerLieutenantsJohn Peat; William Braidwood jnr; Charles Ritchie jnr; Robert Stevenson; Thomas Hamilton; Matthew Sheriff; Adam Brooks; John Yule; John Cameron EnsignsJohn Menzies; David Robertson; Andrew Wilson; John Grieve; William Woodburn; John BallantineChaplainRev. Alexander BruntonSurgeonWilliam Farquharson; Thomas Lothian (assistant)Sergeant MajorGeorge Neagle

Named officers holding commissions in the Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen, at the time of its establishment, Gazetted Nov 1803- January 1804.

It was all very Dad’s Army, but at this time the fear of invasion was genuinely held as a result of intense newspaper speculation. Matters came to a head on January 31st 1804 when the Volunteers of Hawick and Teviotdale rose to repel an “invasion” after the lighting of the chain of hilltop warning beacons across the Borders counties. This proved to be a false alarm, the result of an inexperienced but enthusiastic watchman at Hume Castle near Kelso who saw a distant glow on the eastern horizon – actually charcoal burning at Shoreswood in Northumberland, 15 miles away – and thought it was the beacon at Dowlaw being lit.

“A Hilltop Beacon”, William Bell Scott, 1828. National Galleries of Scotland

It was not until the Scottish volunteer companies arrived at Berwick-upon-Tweed the following morning after marching excitedly through the night that the mistake was realised, but a celebration was held never-the-less to mark the efficacy of the warning system and the enthusiasm of the response. It was only a sceptical naval watchkeeper at the St. Abb’s Head signal station that prevented the warning being transmitted all the way to the end of the chain at Edinburgh.

Hey, Volunteers are ye wauking yet? Ho, jolly lads, are ye ready yet? Are ye up, are ye drest, will ye all do your best? To fight Bonaparte in the morning!

Now, brave Volunteers, be it day, be it night; When the signal is given that the French are in sight; Ye must haste with your brethren in arms to unite; To fight Bonaparte in the morning!

Marching song of the Dunfermline Volunteers, to the tune of the traditional “Hey, Johnnie Cope”

Despite the Government’s approval, as supernumaries the Spearmen had to finance themselves. In February 1804 a public subscription was raised to cover the expenses of fitting out the unit, the Caledonian Mercury reporting “there can be little doubt that it will soon exceed the sum required“. The Town Council voted fifty Guineas towards the cause as did the Association for the Defence of the Firth of Forth, the Incorporation of Goldsmiths and the United Incorporations of Mary’s Chapel (the Wrights and the Masons). The Incorporation of Tailors and the Bakers provided thirty each, those of The Hammermen twenty-five, The Fleshers twenty and The Hammermen of Canongate five. A number of town councillors and many of the founding officers also contributed, as did some notable local patrons. A Benevolent Society was set up by the officers to provide “mutual aid of each other in the event of sickness or death” in September of that year and which would later be extended to all the Volunteers of the city.

Public subscriptions to the Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen (L.E.S.), giving a good indication of the demographic of the principal backers. Caledonian Mercury, 9th February 1804

They used as their parade ground the Heriot’s Hospital green, that traditionally used by the other Volunteers in the city and seen in the background of the portrait at the top of the page of Sergeant Patrick Gould. In 1805 they were formally recognised by the Home Secretary, Lord Hawkesbury, as a full member of the Corps of Volunteers. This gave them equal status with the city’s other volunteer units and entitling them to receive Government funding, pay and arms. It is likely at this time they traded in their pikes for Government-issue muskets. To mark the occasion, “this band of citizen warriors had their stand of colours delivered to them on the 12th August 1805″ (the birthday of the Prince Regent, the Prince of Wales). These were provided and presented by the wife of the Lieutenant Colonel Bennet and her daughter Miss Scott of Logie. Chaplain Rev. Brunton consecrated them with “a most impressive prayer” after which the batallion marched out of the city to Duddingston House, the residence of the Earl of Moira, Commander-in-Chief of the Army in Scotland. The Earl inspected the formation after which they returned to the Bennet household on Nicolson Street where “they were regaled by him in a very liberal and handsome style of hospitality“.

The Earl of Moira, Addressing the Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen. John Kay caricature, 1805. In the background is Duddingston House, Moira’s residence in Edinburgh, where the Spearmen marched for inspection following receiving their colours at Heriot’s Hospital

In the event of the Spearmen being called out, they were to assemble upon the Mound as their chosen “alarm post in case of invasion or popular tumult“. In March 1804 a battery of artillery was added, armed with two experimental 6-pounder cannons designed and built by Mr Roebuck of the Shotts Iron Company. The guns were commanded by Captain William Braidwood jnr and were provided with two novel ammunition carts, designed to be pulled by domestic draught horses.

Caricature of an Edinburgh volunteer artillery officer and his piece, which is similar to that shown on the medal at the top of the page. The Spearmen were not the only volunteer artillery in the city, so this may or may not represent Captain William Braidwood. By J. Jenkin, 1805. National Library of Scotland.

The artillery would get the Spearmen into trouble with the law. On Monday 25th September 1805, eager to demonstrate their efficiency and readiness to the city after formally receiving their colours, they marched and drilled through the streets before assembling on the Mound to firing off a number of volleys in salute from the Roebuck Guns. After the third and final blast, Lieutenant Colonel Bennet was apprehended with “violent passion” by John Tait, judge of the City Police Court and superintendent of the newly instituted Police Office. Tait threatened “at your peril remain on this ground a moment and if I ever see you and your Corps on the streets of Edinburgh again, it shall be at your peril“.

“An Eminent Judge… of Broom Besoms!!!”. While this caricature by John Kay represents a well known old peddlar of brooms, it satirises instead John Tait, the Judge of the Police Court and Superintendent of Police, who had accosted the Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen. National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D16508

Bennet wrote to Sir William Fettes, the Lord Provost and Lord Lieutenant of the City, to complained that he and his men had been prevented by the civilian authorities from carrying out their duties and were treated with “gross and repeated insults from an immense mob“. He threatened that he would have to disband the unit if they could not go about their business unmolested. Tait had only been in his position of authority a few months and was likely trying to publicly demonstrate that it was he, and not any Volunteers, who was responsible for law and order. He wrote back to the Lord Provost standing his ground, but making the clarification that it was only firing off cannons in public that he wished to prevent, and not their marching and drilling. This seemed to placate both sides and thereafter Spearmen got on with tier duties of playing at soldiers.

“Guard Room Tactics, Bugs in Dander; or a Volunteer Corps in Action.” 1798 caricature lampooning the Volunteers, by Charles Ansell. The Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen were dressed in a very similar fashion. Yale Centre for British Art B1981.25.1158, via Wikimedia

On September 1807 they changed their name to the Loyal Edinburgh Volunteers to acknowledge their changed status (which causes confusion with the Royal Edinburgh Volunteers, who they remained distinct from) and also that thanks to Moira’s intervention they had retired their spears and were now properly armed with muskets. They marked their promotion by marching to Alloa for ten days on “active duty”. The Caledonian Mercury reported that “their conduct on the march to and from Alloa, and while in quarters, was orderly and regular in the highest degree, and their attendance at drill, for seven hours every day, was unremitting“.

“Light Infantry Volunteers on a March”. 1804 satirical cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson lampooning the physical condition of Volunteer units. Picture via Miesterdrucke.ie

The experience must have been enjoyable as they then applied to be transferred into the Militia, an offer which was rejected. Undeterred, in December that year it was announced that the Prince of Wales had “been graciously pleased to accept an offer… of an extension of their services to any part of Great Britain” and as such they would henceforth be known as the Prince of Wales’ Loyal Edinburgh Volunteers. This was far removed from their founding aim of serving only in the city; things may have gone to their heads as in 1809 the entire Volunteer forces of Edinburgh offered their services to go to Spain and fight alongside the regulars in the bloody Peninsular War. Again the offer which was politely declined.

“Loyal Britons Lending A Lift”, a British soldier assisting the Spanish in fighting the French. August 1808 caricature by James Gillray.

Lieutenant Colonel Inglis remained in charge of the renamed Spearmen until the volunteer forces were officially disbanded on July 11th 1814. They have been largely forgotten about and even in their own time were in the shadow of the Royal Edinburgh Volunteers and the Yeomanry, but at least one unknown amateur poet penned a verse in their honour, although it is hardly complementary.

It is weel Kend these guy wheen years

I’ve praised our Royal Volunteers

The Spearmen has appeared at last

O’ them we should hope the best.

There’s numbers o’ them without doubt

They are baith souple louns and stout,

But other o’ they I do ken

Dude help them poor auld worn out men

An’ I wad scorn to tell a lee

They’re neither fit to fight nor flee

An’ other some raw mou’d callants

I’ve seen far better selling ballants.

What brings them out in name of wonder

Wer it no to make a gudly number.

O’ them the brethern may think shame

Far better they wad stay at hame.

Poem to the Loyal Edinburgh Spearmen, 1804

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#Army #AuctionHouseArtefact #Edinburgh #Georgian #JJenkin #JohnKay #Military #Napoleonic #Policing #Revolution #TownGuard #Volunteers