🌿 (buffy)² 🌿 wants to read The Holy Hour

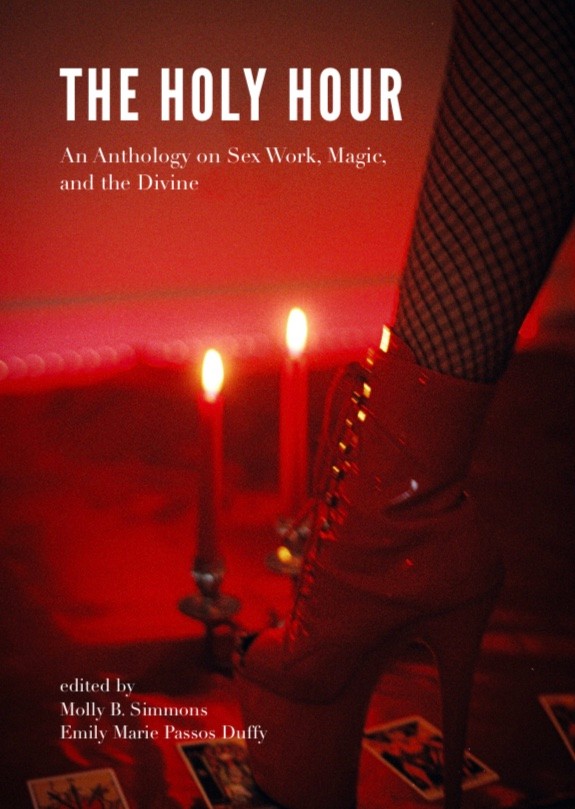

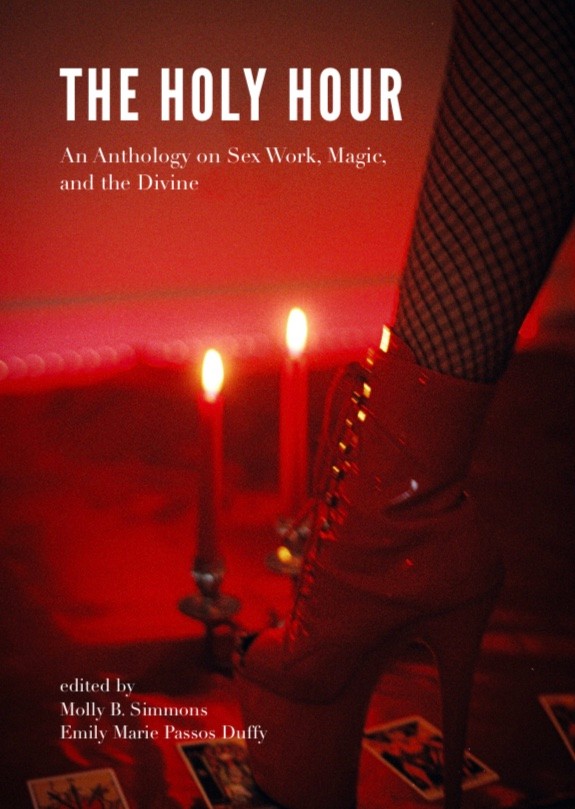

The Holy Hour

The Holy Hour: An Anthology on Sex Work, Magic, and the Divine is a multi-media collection of art and writing …

political thembo • they/them • enthusiastic zinester & artist • located in Berrin, South Australia • disabled • tech policy • reluctant security engineer • future subsistence farmer

This link opens in a pop-up window

Success! 🌿 (buffy)² 🌿 has read 14 of 12 books.

The Holy Hour: An Anthology on Sex Work, Magic, and the Divine is a multi-media collection of art and writing …

One day in 2004, Gardiner Harris, a pharmaceutical reporter for The New York Times, was early for a flight and …

I actually think that if you're a computer person who loves crafts, or a craft person who loves computers you'll get something out of this book. Having a look through the table of contents and a skim of some of the essays it looks like it covers a good intersection of tech x craft.

It's probably also super relevant to critiquing AI in the arts and craft space... looking at you AI generated cross-stitch patterns.

I actually think that if you're a computer person who loves crafts, or a craft person who loves computers you'll get something out of this book. Having a look through the table of contents and a skim of some of the essays it looks like it covers a good intersection of tech x craft.

It's probably also super relevant to critiquing AI in the arts and craft space... looking at you AI generated cross-stitch patterns.

Should I be finishing Bullshit Jobs for presentation preparedness? Yes. Am I doing that? No.

Should I be finishing Bullshit Jobs for presentation preparedness? Yes. Am I doing that? No.

Playing dead is an exploration of "pseudoside", the act of faking one’s death. Elizabeth Greenwood explores the phenomenon through a variety of lenses: interviewing people who have attempted it, those who help people disappear, and the people involved investigating death fraud.

What struck me was most of the stories were about men. Men seeking escape, reinvention or fortune. Greenwood touches on this toward the end of the book, but only briefly, and I wish there was a deeper consideration of why pseudoside seems so gendered.

For most part, the book kept me engaged right up until the prologue, what frustrated me in the wrap up was Greenwood’s use of a Plato quote: “justice consists in speaking the truth and paying one’s debts.”

It feels like despite going to such great lengths to understand death fraud, Greenwood has overlooked why people actually commit death fraud -- to escape …

Playing dead is an exploration of "pseudoside", the act of faking one’s death. Elizabeth Greenwood explores the phenomenon through a variety of lenses: interviewing people who have attempted it, those who help people disappear, and the people involved investigating death fraud.

What struck me was most of the stories were about men. Men seeking escape, reinvention or fortune. Greenwood touches on this toward the end of the book, but only briefly, and I wish there was a deeper consideration of why pseudoside seems so gendered.

For most part, the book kept me engaged right up until the prologue, what frustrated me in the wrap up was Greenwood’s use of a Plato quote: “justice consists in speaking the truth and paying one’s debts.”

It feels like despite going to such great lengths to understand death fraud, Greenwood has overlooked why people actually commit death fraud -- to escape their debts and obligations. It seems like she missed the opportunity to really interrogate or understand how oppressive debt systems can be. Historically, debt relief was common, and the extreme measures people take to escape financial obligations often reflect systemic pressures more than personal moral failings.

That said, Greenwood never claims to be writing a sociological study of economics and work. It's a book about death fraud and on that level it's good: it’s entertaining, informative, and offers a look at one of society’s more bizarre escape fantasies.

This short book demystifies how the two systems of technology and capitalism work together and equips readers with practical tools …

One day in 2004, Gardiner Harris, a pharmaceutical reporter for The New York Times, was early for a flight and …

One day in 2004, Gardiner Harris, a pharmaceutical reporter for The New York Times, was early for a flight and …

One day in 2004, Gardiner Harris, a pharmaceutical reporter for The New York Times, was early for a flight and …

Is Tasmanian salmon one big lie?

In a triumph of marketing, the Tasmanian salmon industry has for decades succeeded …

The true story of the greatest conspiracy in U.S. history - and how to fight back.

Have you ever …

Birds Aren't Real is one of the first audiobooks that I've listened to that is made for the audiobook format so it includes audiobook centric comments and additional background noises which I feel made the audio book a lot more immersive than other books I've listened to.

That aside if this book wasn’t under the “comedy” section of non-fiction you could easily mistake this book as encouraging conspiracy culture. From the outside it's not clear from the content that it's a nonsensical movement led by Peter McIndoe. I personally picked it up thinking it was a book about the "Birds Aren't Real" movement as a gateway conspiracy? You know the silly simple ones that get people hooked -- like wellness culture and white supremacy.

And here's the thing once you get past the books administrative preamble it's obvious it's satire, but when you put into context that there …

Birds Aren't Real is one of the first audiobooks that I've listened to that is made for the audiobook format so it includes audiobook centric comments and additional background noises which I feel made the audio book a lot more immersive than other books I've listened to.

That aside if this book wasn’t under the “comedy” section of non-fiction you could easily mistake this book as encouraging conspiracy culture. From the outside it's not clear from the content that it's a nonsensical movement led by Peter McIndoe. I personally picked it up thinking it was a book about the "Birds Aren't Real" movement as a gateway conspiracy? You know the silly simple ones that get people hooked -- like wellness culture and white supremacy.

And here's the thing once you get past the books administrative preamble it's obvious it's satire, but when you put into context that there are also people who think that the New York City Police Department had discovered a paedophilia ring operating out of Comet Ping Pong... you can sort of see how this book could blur the line between fact and fiction for some people. The morals of satire behind us, one of the most compelling parts of this book (at least for me) is if you've ever wondered what it feels like to rapidly fall into a conspiracy rabbit hole, and have your mind swirling with thoughts that are rooted in reality but also make you question everything you know... this is the book that simulates that feeling.

I never thought I'd find myself looking up whether bird-less eggs were real (they are) but here we are!

Because each chapter is relatively short and fast paced it feels like watching your Republican Uncles playlist of QAnon videos but instead of explaining how there is a cabal of Satanic, cannibalistic child molesters in league with the deep state the cabal is responsible for killing all the birds to replace them with government surveillance birds and it's your job, dear patriot to help repopulate the decimated bird population.

Chapter 5 is literally just the author describing each of the American presidents... and often telling us how handsome he thinks they are. I feel like this book is like a falling into conspiracy culture simulation?

I have no idea what is going on, but I fear this is what my brain is going to remember about American presidents.