Derek Caelin finished reading Apollo 13 by Jim Lovell

Apollo 13 by Jim Lovell

Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13 (published in paperback as Apollo 13), is a 1994 non-fiction book by …

Seeking a Solarpunk Future

Sci Fi | Cozy Fic | Sustainable Living | Classics | Green Energy | He/Him/His.

This link opens in a pop-up window

92% complete! Derek Caelin has read 46 of 50 books.

Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13 (published in paperback as Apollo 13), is a 1994 non-fiction book by …

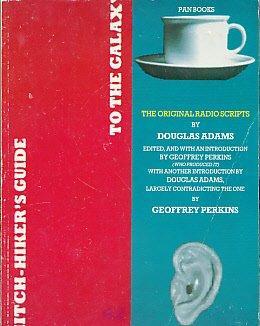

Adams D & Perkins G (Ed)

There is a sense of grief pervading the book. A beautiful thing has been lost, is being lost, will be lost, unless we change. We seem no closer to achieving this goal today than we were when this book was first published in 1948, scant years before the author died fighting a prarie fire.

A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There is a 1949 non-fiction book by American ecologist, forester, and environmentalist …

The key-log which must be moved to release the evolutionary process for an ethic is simply this: quit thinking about decent land-use as solely an economic problem. Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and esthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient. A thing is ight when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 224)

In all of these cleavages, we see repeated the same basic paradoxes: man the conqueror versus man the bíotíc citizen: science the sharpener of his sword versus science the searchlight on his universe; land the slave and servant versus land the collective organism. Robinson's injunction to Tristram may well be applied, at this juncture, to Homo sapiens as a species in geological time: Whether you will or not You are a King, Tristram, for you are one Of the time-tested few that leave the world, When they are gone, not the same place it was. Mark what you leave.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 223)

A land ethic, then, reflects the existence of an ecological conscience, and this in turn reflects a conviction of individual responsibility for the health of the land. Health is the capacity of the land for self-renewal. Conservation is our effort to understand and preserve this capacity.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 221)

To sum up: a system of conservation based solely on ecnomic self-interest is hopelessly lopsided, It tends to ígnore, and thus eventually to eliminate, many elements in the land community that lack commercial value, but that are (as far as we know) essential to its healthy functioning. It assumes, falsely, I think, that the economic parts of the biotic clock will function without the uneconomic parts. It tends to relegate to government many functions eventually too large, too complex, or too widely dispersed to be performed by government. An ethical obligation on the part of the private owner is the only visíble remedy for these situations.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 215)

Land-use ethics are still governed wholly by economic self-interest, just as social ethics were a century ago.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 209)

We all strive for safety, prosperity, comfort, long life, and dullness. The deer strlves with hís supple legs, the cowman with trap and poison, the statesman with pen, the most of us with machines, votes, and dollars, but it all comes to the same thing: peace in our time. A measure of success ín thís is all well enough, and perhaps is a requísite to objective thinking, but too much safety seems to yield only danger in the long run. Perhaps this is behind Thoreau's dictum: In wildness is the salvation of the world. Perhaps this is the hidden meaning in the howl of the wolf, long known among mountains, but seldom perceived among men.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 133)

It is a century now since Darwin gave us the first glimpse of the origin of species. We know now what was unknown to all the preceding caravan of generations: that men are only fellow-voyagers with other creatures in the odyssey of evolution. This new knowledge should have given us, by this time, a sense of kinship with fellow-creatures; a wish to live and let live; a sense of wonder over the magnitude and duration of the biotic enterprise.

Above all we should, in the century since Darwin, have come to know that man, while now captain of the adventuring ship, is hardly the sole object of its quest, and that his prior assumptions to this effect arose from the simple necessity of whistling in the dark.

These things, I say, should have come to us. I fear they have not come to many.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 109 - 110)

Men still live who, in their youth, remember pigeons. Trees still live who, in their youth, were shaken by a living wind. But a decade hence only the oldest oaks will remember, and at long last only the hills will know.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 109)

Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language.

— A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold (Page 96)

A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There is a 1949 non-fiction book by American ecologist, forester, and environmentalist …