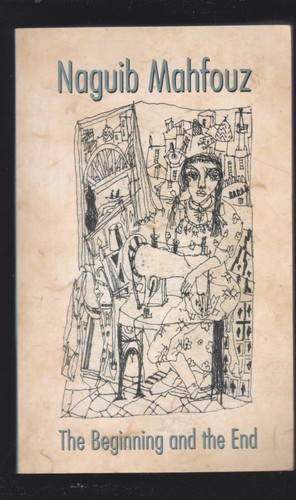

Fionnáin started reading The Beginning and the End by Naguib Mahfouz

I found this in a very nice second hand bookshop and had wanted to read Mahfouz for a while, thinking I had never read his work. I later remembered that I had read Miramar years ago. I left this one on the shelf for a while, but picked it up when I wanted a novel recently.