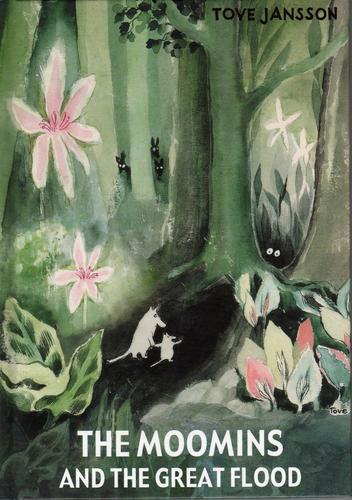

mouse finished reading The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson (Mumintrollen, #1)

The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson, David McDuff (Mumintrollen, #1)

The Moomins and the Great Flood is the first book about the Moomins, originally published in 1945. It´s the story …