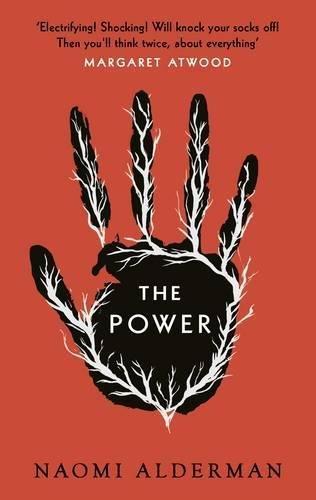

Eduardo Santiago reviewed The Power by Naomi Alderman

Review of 'The Power' on 'Goodreads'

5 stars

I knew the basic premise, thought I knew what to expect, but even so this book knocked me over. Surprisingly well developed: Alderman clearly thought the whole thing through. Over and over she tosses in twists that make perfect sense in hindsight, some fun, some very much not, most of them deserving of a pause for the reader to digest, few of them succeeding in that because the tension is so high. It was fun: enjoyable reading, and a memorable worldviewtopsyturvification that keeps me still wondering: what if?

There's a lot to gripe about: the hearing-voices gimmick didn't work for me, and there are rather a lot of eyeroll moments, but none of that mattered. I fell for the characters, fell hard for the story and the what-ifs. Just ramp up your suspension-of-disbelief filter to five or six, accept the wild improbabilities, and move along. Pause and wonder …

I knew the basic premise, thought I knew what to expect, but even so this book knocked me over. Surprisingly well developed: Alderman clearly thought the whole thing through. Over and over she tosses in twists that make perfect sense in hindsight, some fun, some very much not, most of them deserving of a pause for the reader to digest, few of them succeeding in that because the tension is so high. It was fun: enjoyable reading, and a memorable worldviewtopsyturvification that keeps me still wondering: what if?

There's a lot to gripe about: the hearing-voices gimmick didn't work for me, and there are rather a lot of eyeroll moments, but none of that mattered. I fell for the characters, fell hard for the story and the what-ifs. Just ramp up your suspension-of-disbelief filter to five or six, accept the wild improbabilities, and move along. Pause and wonder once in a while. Then put yourself to work building a world with fewer power imbalances.